Banerjee's Blog

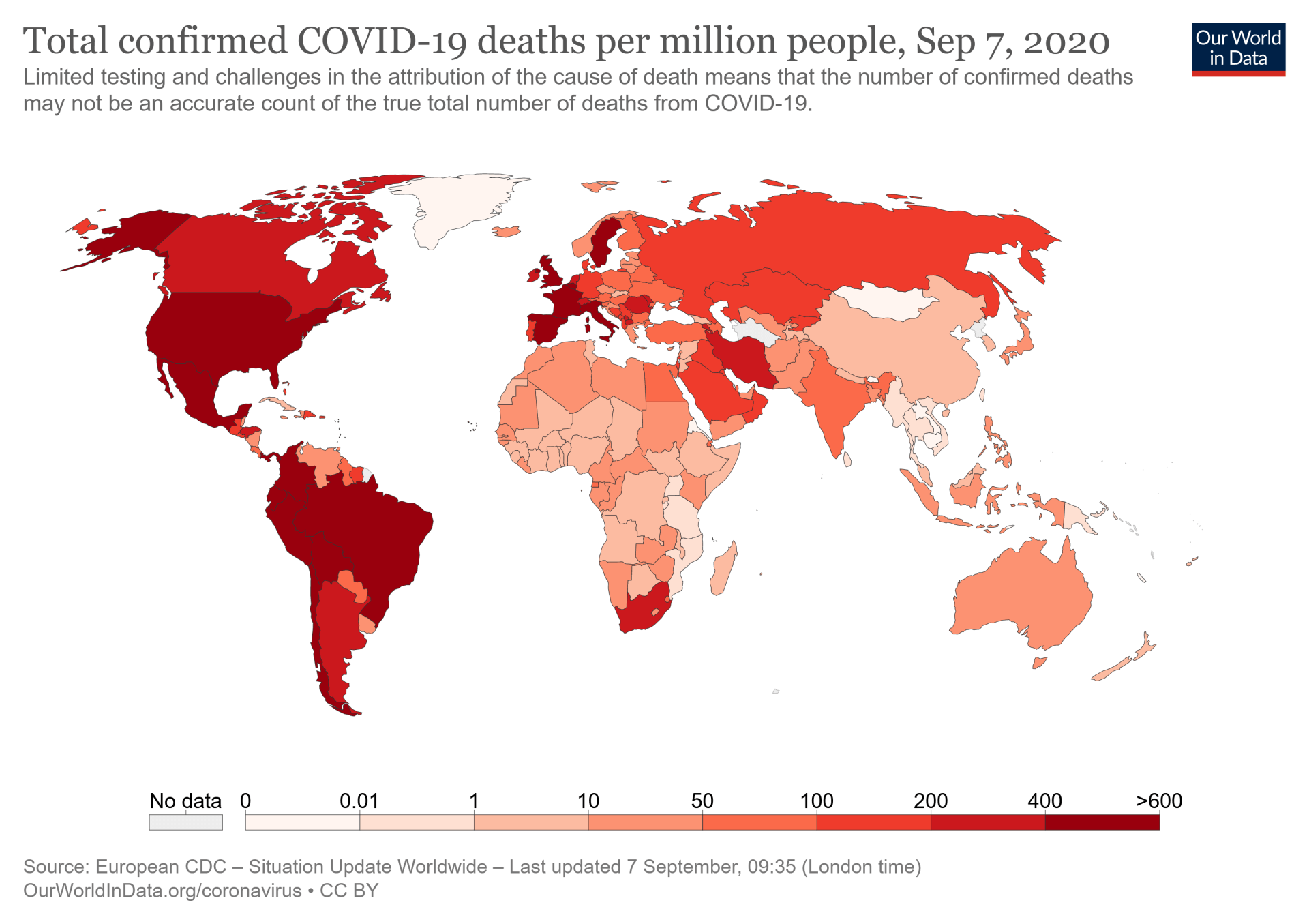

In his seminal paper, “Sick individuals and sick populations” , the epidemiologist, Geoffrey Rose, famously said, “The corresponding strategies in control are the ‘high-risk ’ approach, which seeks to protect susceptible individuals, and the population approach, which seeks to control the causes of incidence.” Two camps have emerged in the policy debate, which broadly follow Rose’s different approaches with respect to coronavirus (COVID-19), with two opposing public statements. The Great Barrington Declaration , which is broadly anti-lockdown and pro-“herd immunity”, believes that only “high-risk” groups should be shielded and the rest of society should resume normal life. The John Snow Memorandum (which I have signed) believes the only scientific response is to suppress COVID-19 at population level in order to avoid a cycle of repeated lockdowns. This week, the Lancet editor, Richard Horton states, “ On some of the most important measures of health, the four nations of the United Kingdom perform worse than our nearest neighbours. Even with coronavirus out of the picture, Britain is the sick man, woman and child of Europe.” He quoted our work, published in the Lancet in May, which showed that the at-risk population for mortality was much larger than the 1.5 million who were shielded during lockdown. We know that countries that have acted quickly and had stringent measures have had lower rates of excess COVID-19 deaths. Early on, the WHO gave a clear steer that test, trace and isolate was the way to tackle the pandemic, and we know that such systems need to be functioning well to keep the spread of the virus down. The indirect effects of COVID-19, whether on cancer , cardiovascular disease or obesity are expected to be greater if the infection rate is high, so the choice is not between economy and public health, or between cancer services and keeping infection rates down. The herd immunity camp ignores the fact that high infection rate will give the worst of all worlds. Horton is arguing that both COVID and non-COVID care are reliant on population approaches where the UK is struggling. “Low risk” individuals can become “high risk” in terms of becoming infected and spreading the infection. 10% of people are responsible for 80% of transmission. Moreover, in our study (preprint, not yet peer reviewed) in 201 individuals with persistent symptoms a median of 4 months after initial symptoms of COVID-19, we found evidence from whole body MRI scans to suggest high symptom burden and mild impairment in single and multiple organs in 66% and 25% respectively. The cohort had a mean age of 44, and was low risk in terms of risk factors (hypertension: 6%; diabetes: 2%; heart disease: 4%) and hospitalisation with COVID-19 (18%). These are preliminary data and we will be following up over time. As the debate continues and the science emerges about the exact definition and natural history of long COVID, we can agree that SARS-CoV-2 infection may have long-term consequences, even in individuals at low risk of mortality. Herd immunity rests on the idea that most people have low risk with respect to COVID-19. That may be the case with respect to deaths ( where 95% have occurred in those who are >70 years or with underlying conditions ), but may not hold true in terms of risk of infection or longer-term morbidity. If we are not sure about who is actually low or minimal risk, or rather very few people are at low risk, the population approach is the only one that the science supports and that we can sensibly follow.

I entered lockdown six days early, when the UK had 1950 cases and 81 deaths from coronavirus (COVID-19). Mine was driven partly by concerns that we were not following lessons from Wuhan, but mainly by a question that day in my clinic from a long-standing patient with heart failure. I often said he was fitter than me, so he was confused at being “high-risk” (now “ clinically vulnerable ”), as per the list of conditions announced on 16th March, recommending stricter “social isolation”. Every affected country reported increased deaths with old age and certain conditions like heart disease. I wanted to communicate his individual risk. I wanted to investigate whether risk of death differed between conditions on the government’s list, from chronic kidney disease to diabetes, to check we were isolating the right people. Finally, I suspected unchecked infection rates would create thousands of deaths. My lockdown was with my laptop. I did not see my family for four days. By 20th March, our four-strong research team (Laura Pasea, Spiros Denaxas, Harry Hemingway and I) had convinced twelve colleagues to join us in this research. Everybody contributed with skills from virology to statistics via phone calls, emails and Microsoft Teams, which I had only just discovered. On the same day that a further “ extremely vulnerable ” list of conditions was declared, we published our preprint on 22nd March, after sending to the Chief Medical Officer’s office. The new list included 1.5 million individuals who should stay at home for at least 12 weeks (“shielding”), including those on chemotherapy. The following evening, the Prime Minister announced lockdown, now easing. We showed that 10% infection rate (likely in March/April) would lead to 30,000 and 70,000 excess deaths over one year, only preventable by reducing infection rate. With refinements, we published in The Lancet on 12 May, showing 20% of UK adults are “high risk”. Twelve weeks after lockdown, there are at least 287,399 confirmed cases and 40 597 deaths, now including colleagues, friends and several patients. I am in a family of strong women. My wife, a dentist at home during lockdown, prepares to return to work as the curve flattens, PPE supplies improve and clear professional guidance emerges (dentistry is among the highest risk professions). She is home-teacher to our 6-year old daughter (the other strong madam in our house). There is another strong woman I am missing. My mother, in her sixties with diabetes, is in Yorkshire, socially isolating with my father. Since the Prime Minister’s announcement on 11 May, she wanted to know if and when she should return to teaching. She asked if my exercise, now unlimited, might lead me up North from Barnet (with her granddaughter of course). The first question was easier to answer and the actions of Mr Cummings introduce doubt at best. Whereas we have guidance for extremely vulnerable individuals, it is confusing for people like my mother, who represent a larger proportion of the population. 90% of excess deaths occur in this category. Moreover, care of underlying conditions is likely to have been reduced, probably due to patients not attending hospital and health system strain. To avoid further tragedy, we must focus our efforts here, protecting them from infection and ensuring treatment of their comorbidities. We urgently need to communicate risk, regardless of COVID-19, to patients, carers, researchers and policymakers. During intensive care shifts at the Nightingale Hospital, I saw how evidence could help conversations with relatives in difficult times. We started to address this gap with a free online calculator , allowing people to put in their age, sex and underlying conditions and see their individual risks. This is the beginning of the journey. We will revise and refine as more data become available. Our research group has grown. Like all academics globally, we are looking down the back of the sofa for data, people and funds to help our research which never needed to be done so quickly. Although we could access health records from 3.8 million individuals for research, that is still only 5% of the UK population. Perhaps we need to reflect on health data which should be accessible for urgent and sometimes immediate research in public health emergencies. Data has long been labelled the “new oil”. Much more than that, it could be the “new drug” or the “new vaccine”.

Around the world, researchers are working around the clock at unprecedented pace to do something about COVID-19. In terms of therapies, there are two avenues being explored: drugs and vaccines. The scale of the challenge facing health systems in all countries means that governments, health professionals and the public are keen to find quick wins which can urgently show benefit for patients. The news over the weekend was remdesivir, which was published in the New England Journal of Medicine , one of the most prestigious medical journals, and was all over the headlines as an advance in COVID-19 therapy. Even the US President was talking about it. “Repurposing” of existing drugs is likely to be quicker than developing new compounds. Remdesivir had originally been pushed through rapid approval during the Ebola epidemic , but is inferior to other treatments such as monoclonal antibodies. In the study (not a randomised trial), 61 individuals were given at least one intravenous dose of remdesivir for “ compassionate use ”, which is where drugs are provided in the absence of any other treatment options, often in the palliative care setting - “ a gift from God ” in Mr Trump’s words. Only data from 53 patients could be analysed. Overall the authors report a “clinical improvement” in 36 of the 53 patients. Thirty of these patients were ventilated, and four received ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation), which is where blood is oxygenated outside the lungs. 25/53 patients were discharged from hospital, and 7 died (6 of whom had been ventilated). We cannot lower the bar for science and evidence just because we are in the middle of a public health emergency across the globe. I cannot count all the biases involved in this study but I will list a few. The study is funded by Gilead, the drug manufacturer, which is sponsorship bias , which affects the design and conduct of the research. The 61 patients came from 9 countries (including the US, Canada, Europe, and Japan) which is a selection bias , making the included patients unlikely to be representative. There were no controls in the study. The reporting of the results in the media undoubtedly exhibits a spin bias , where results are over-hyped . There is loss to follow-up since 8/61 (13%) of patients were not included in the data analysis. There needs to be a proper randomised trial before we can even consider using this drug with patients following COVID-19 infection. As Sir Jeremy Farrar, Director of the Wellcome Trust, said last week, “ The only exit from this pandemic is through science ”. However, it is better to do less COVID-19-related science, and ensure that it is high-quality in design and conduct, as well as driven by the right motivation.

High Risk, High Reward Over the last week, I have been working with a team of incredible individuals to establish the Nightingale Hospital in London. I am a small cog in a large engine, but helping with perhaps the most important thing after the patients - the data. We have talked about “ learning health systems ” for some time, where data flowing through the health care system ensure that science, evidence and care are continuously connected and continuously improving. The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, affecting every country in the world, has already shown how important this concept is, and will be, to push forward our knowledge and our healthcare. Even the simplest epidemiology needs to be defined for this disease. For example, data from 799 individuals, including 113 who died with COVID-19 in Wuhan, published this week, can tell us about prevalence, the proportion of cases with particular characteristics. Prevalence needs to be defined in order to understand the patients that are at potentially highest risk. As a cardiologist, I am interested in the fact that hypertension (48% vs 24%), cardiovascular disease (14% vs 4%), and cerebrovascular disease (4% vs 0%) were much more frequent patients who died than those who recovered. Prevalence can also be helpful at looking at the complications from COVID-19.

Dr Ami Banerjee discusses his COVID-19 study and its implications Countries as different as France, China and India have been put into lockdown, with enforcement of social distancing . Our analysis showed why the UK urgently needed to follow, and we released to preprint server on 22 March. On the evening of 23rd March, the Prime Minister announced the UK was in lockdown. We’ve got no evidence that the virus is behaving differently here, no evidence that people were obeying voluntary measures more because British people are more obedient. The public should ask what is so different about Britain and the British people that we should be behaving so differently from almost every other country on the globe. As a frontline clinical academic, I am already experiencing a dramatically changing workload during the coronavirus pandemic and our study shows what is at stake. There are three moving parts in models of deaths from coronavirus. First, the background risk tells us which deaths would have happened even in the absence of coronavirus. Second, the impact of the virus compared with background deaths; for example, winter flu causes about a 20% increase in deaths each year. Third, the infection rate, or the proportion of people infected with the virus. We can’t change how fatal the virus is and we can’t stop people having heart disease or lung conditions. The only factor we can change quickly is the infection rate in the population. Our study used NHS health records in 3.8 million people led from University College London and Health Data Research UK, and was turned around in 72 hours, motivated by the pressing need to provide the public, researchers, policymakers and health professionals with tools to model excess deaths in the people at high-risk at varying rates of infection. Our model incorporated the background risk from individual patient data, based on their underlying conditions such as heart disease and chronic lung disease. It also considered a best case where the virus has a similar impact to winter flu, which is highly unlikely, and a worst case where it doubles the death rate. We modelled four levels of infection: 1 in 100,000 people (“stringent” or “full suppression”), 1 in 100 (“partial suppression”), with voluntary social distancing and school closures, 1 in 10 (“mitigation”), the strategy until 10 days ago with education of the public and social isolation of cases, and 8 in 10 people (“do nothing”). They found that the previous mitigation strategy aiming to slow the spread of coronavirus could lead to 35,000 extra deaths over 1 year, even if it carried the same risk as winter flu. In the partial suppression scenario (until this week), there would be 6896 deaths if the virus carried double the risk, which is likely to be an underestimate given the strain on healthcare systems, not least intensive care units. However, with full suppression (where we are now), the number of total excess deaths could be reduced to hundreds rather than tens or hundreds of thousands. Stringent suppression will work and clearly there is a moral imperative to do this. The data tell us what to do to avoid excess deaths: Full suppression. Full stop. The National Institute of Medicine coined the term, “ learning health systems ” in 2006 to describe the need for data to flow freely between the silos of science, evidence and care to increase quality or efficiency in health systems . For many reasons, the concept has not fulfilled its potential. Used properly, it could ensure high-quality data, timely research and timely care are intimately connected. We know that at undergraduate and postgraduate level, clinicians currently lack specific training in informatics and data science, which we would need to create that learning health system. At Doctor as Data Scientist , we will post blogs, resources and articles every week to illustrate how use of routine data and the learning health system concept is important in public health and healthcare delivery, not least for COVID-19. Dr Ami Banerjee, Associate Professor in Clinical Data Science and Honorary Consultant Cardiologist, UCL